Why bias matters

Because justice matters.

When looking at groups of students in aggregate, there are clear gaps in outcomes for students based on race, ethnicity, gender, disability and class. At the national level, gaps can be found in test scores, annual retention rates, disciplinary measures and graduation rates. Pathways towards STEM careers are increasingly important to many students, families, educators and policy makers, and the STEM pipeline also shows clear gaps in outcomes for students grouped by race, ethnicity, gender, disability and class. More fundamentally, knowledge about STEM and computing is increasingly an important part of power within global online communities and democratic civic engagement.

Field studies across a variety of fields including education, medicine, law enforcement, criminal justice, and housing reveal pervasive discrimination (Bertrand and Duflo 2016). This is especially important when making key decisions that shape other people’s lives like hiring and promotion decisions, and in professions like teaching. These studies provide real-world evidence that “members of a minority group are treated less favorably than members of a majority group with otherwise identical characteristics in similar circumstances,” regardless of whether individuals are prejudiced or intentionally discriminating.

As the MIT Teaching Systems Lab works with K12 educators, teacher preparation programs, and other organizations to scale access to new STEM opportunities, we risk replicating these gaps in areas like computational thinking and making (and even in those machines themselves).

While there has been extensive research in developing and testing theories about the underlying psychological processes that may result in bias in education (eg., Skiba et al. 2002, Blickenstaff 2006), and many promising interventions have been developed (eg., Okonofua et al. 2016, Gehlbach et al. 2016, Forscher et al. 2016, Gregory et al. 2016), additional research is needed to understand how to reduce gaps in K12 student outcomes. Implicit bias, the concept that people may unintentionally or unconsciously act in biased ways, is a promising line of research for understanding how bias might impact teaching and strategies to address it.

Gaps in K12 student outcomes

Keep in mind that while reading about opportunity and outcomes gaps, you may make assumptions about the causes of these gaps (Hetey and Eberhardt 2014). An important question to ask while reading is: why might these gaps in student outcomes exist?

The Coleman Report (1966) was a landmark study investigating the different experiences and outcomes of students from different backgrounds and demographic characteristics. Since that time, educational researchers have extensively documented ongoing differences in the school experience between students based on their race, gender, disability status, and other factors. Even with substantial progress, significant gaps still impact students today.

Black students are more than three times as likely to be suspended or expelled as their white peers (OCR 2016). This difference is visible even in preschool (see Gilliam 2016), and there are important intersectional effects for black female students (Crenshaw 2014). Black and Latino students are 36% of students in schools with calculus, but only make up 21% of students enrolled in calculus (Office for Civil Rights 2016).

While female students are more academically successful in K12 settings than male students, they report liking math and science less than male students (NCES 2015). In upper high school grades, when students have more choice over their course of study, girls opt-out of specific math and science courses (Blickenstaff 2006). For career and technical education programs, girls make up 25% of students in STEM courses (OCR 2012). Within AP courses, more girls make up 61% of biology students and 55% of Environmental Science students, but only 35% of Physics students (all courses) and 23% of Computer Science students (College Board 2016). This is particularly important because students enrolled in AP courses are more likely to major in those subjects in college, especially for STEM subjects (College Board 2014).

Students with disabilities are 12% of all students, but 67% of students subject to restraint or seclusion (OCR 2016). When broken down by class, education achievement beyond high school completion was achieved by 96% of students in high socioeconomic status, but only 72% of students in lower socioeconomic status (Kena et al. 2015).

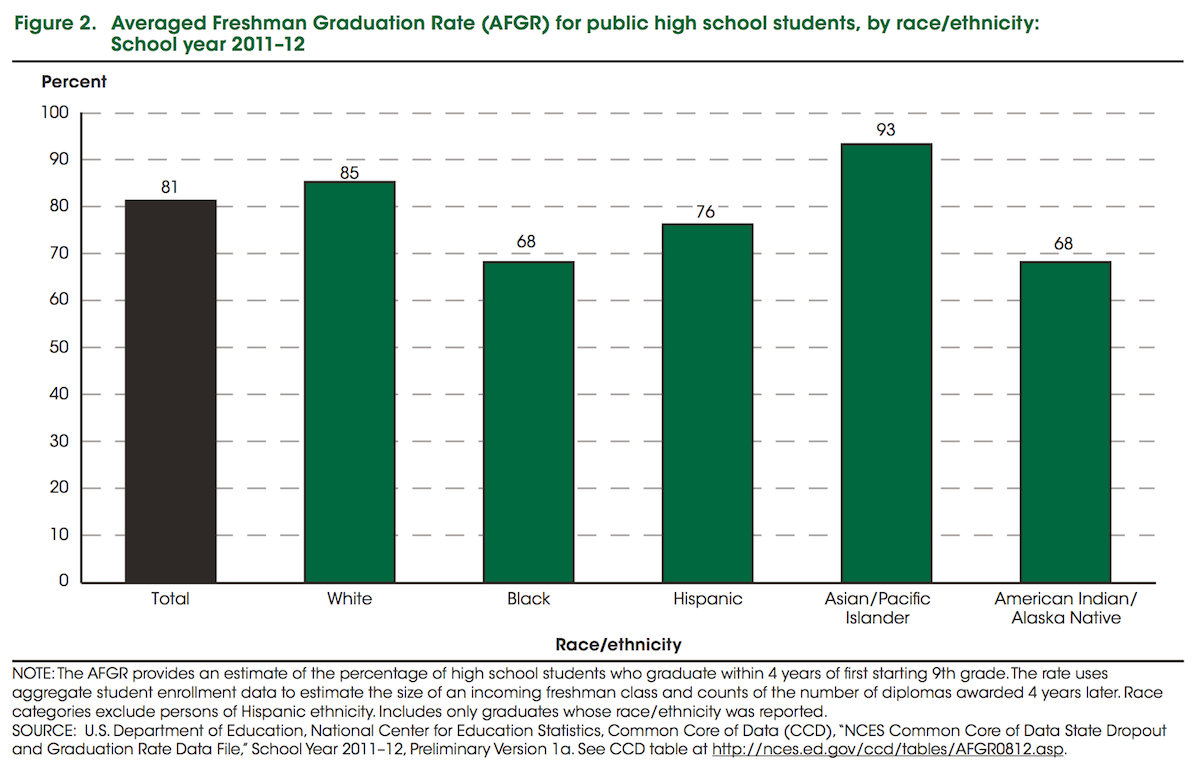

By the end of high school, graduation rates show gaps by race and ethnicity (Kena et al. 2015):

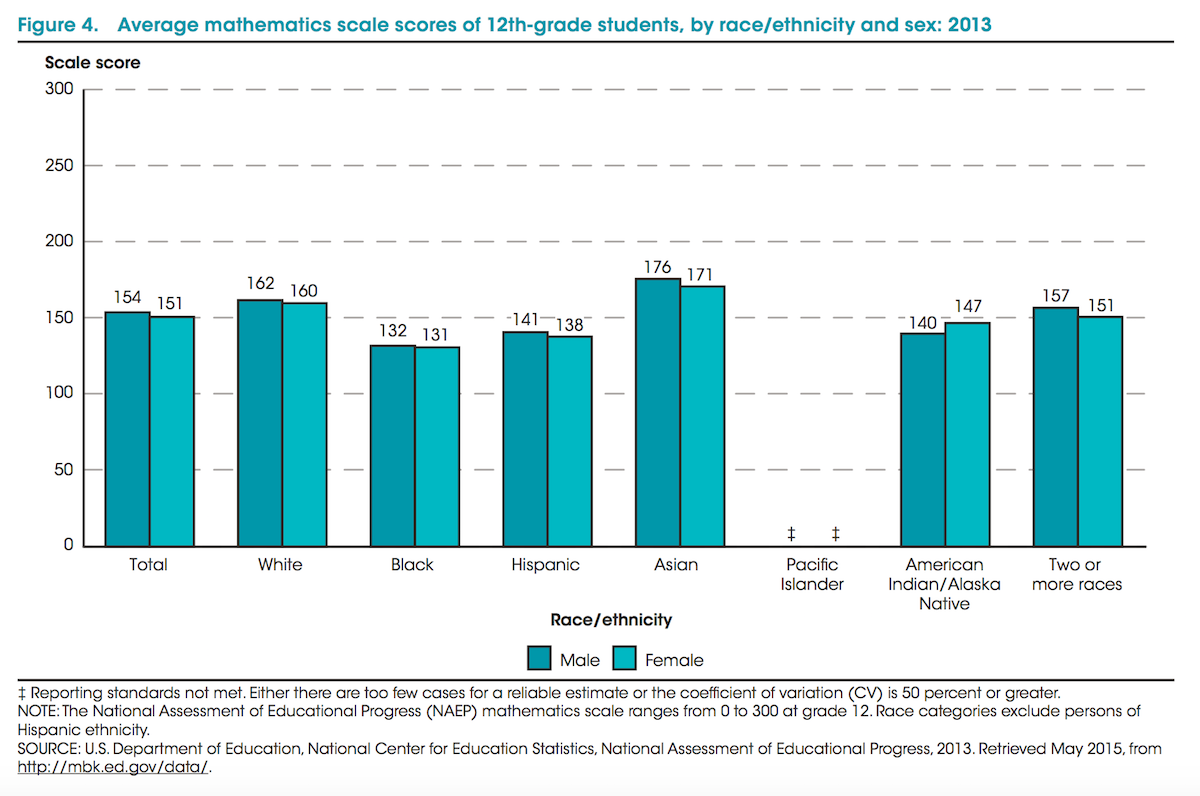

And there are large differences in outcomes on 8th and 12th grade math assessments nationally, when students are grouped by gender and race (Kena et al. 2015):

If these outcome gaps are symptoms, how can we identify and treat the underlying disease? This question is critically important, and there are complex structural, societal and political approaches to answering it, including deficit thinking and implicit assumptions about cultural assimilation (Brandon 2003). Here we’ll focus on teachers, recognizing their place within a system that allows such dramatic outcome gaps to persist.

How bias can surface in teaching

How do students talk about discrimination and bias?

Color Lines has some videos of high school students sharing their own experience of being young black men:

On youcubed, students describe their experiences learning math in school:

Several academic case studies center on student voices and calling attention to their unique perspectives in particular social contexts or academic disciplines. Some starting points for exploring this are:

- Chicana/Latina Testimonios on Effects and Responses to Microaggressions (Huber and Cueva 2012)

- For Computer Science in particular, see: Epistemological Pluralism and the Revaluation of the Concrete (Turkle and Papert 1990)

As you’re listening to student perspectives, a powerful question to ask is: how do my own experiences and values influence how I relate to students’ experience?

How does implicit bias fit in?

While these outcomes show that educators have work to do in terms of equity, it’s complicated to understand all the factors contributing to these different outcomes and challenging to identify what teachers can do to address gaps. One promising line of research from psychology is implicit bias, which has been studied extensively over the last 15 years.

When investigating attitudes towards different groups of people, researchers draw a distinction between attitudes that are measured explicitly (eg., by asking the person to describe their attitude) or implicitly (by measuring how they respond to a particular task). Often implicit attitude measures are done covertly, without the participant knowing that their attitude is being assessed. This approach is appealing because one possibility is that people are hesitant to report unpopular attitudes like racism in explicit measures. This is called the social desirability bias. Another reason implicit attitude measures are interesting is that levels of attitudes like racism and sexism have declined over time using explicit attitude measures (Schuman, Steeh, & Bobo, 1998), yet there are still different outcomes for racial, ethnic and gender groups in many school and work situations – suggesting people’s may espouse egalitarian beliefs while unknowingly behaving in prejudiced ways.

Implicit bias is commonly measured by asking participants to classify different concepts or attributes with different groups of people, and researchers will measure how long the participant takes to do the classification. The most prevalent implicit bias assessment is the Implicit Association Test. Another common approach to measuring implicit bias is to use priming techniques where a participant is shown people from different groups before they complete a task, while researchers measure how their performance changes. These measures have been studied in lab settings extensively, but research into whether it is correlated with or predict behavior is mixed (see most recently Forscher et al. 2016, Forscher et al. 2016, Lai et al. 2016).

What can bias in teaching look like?

We’re working to create learning experiences for teachers that prepare them to create equitable classroom cultures, and also to investigate whether teachers’ behavior is related to measures of implicit bias. Towards this end, we’ve put together an initial set of ways that bias can surface in teaching and would love your input.

How we can improve

Prejudice reduction research suggests that the kinds of interventions that are most promising are: intergroup contact, direct instruction, empathy and perspective taking experiences, accountability and exposure to social norms or experts (Paluck and Green 2009).

How can schools improve?

Within schools, there are some structural changes that can help support teachers and students. Within the Positive Behavior Interventions & Supports system (McIntosh et al. 2014), these include:

- Use Effective Instruction to Reduce the Achievement Gap

- Implement School-Wide Positive Behavioral Interventions And Supports (SWPBIS) to Build a Foundation of Prevention

- Collect, Use, and Report Disaggregated Student Discipline Data

- Develop Policies with Accountability for Disciplinary Equity

- Teach Neutralizing Routines for Vulnerable Decision Points

“Vulnerable decision points” are particularly relevant for pre-service teachers to practice, and research suggests practicing simple “if-then” heuristics may be effective in these situations (Smolkowski et al. 2016, Mendoza et al. 2010).

How can teachers improve?

The most promising interventions with teachers are empathy interventions (eg., Okonofua et al. 2016, Gehlbach et al. 2016) and remote coaching for teachers (Gregory et al. 2016, Gregory et al. 2014). These have been field-tested to assess their real-world impact on outcomes for students. Outside of teaching, the most effective intervention targeting implicit bias in particular is a workshop pairing instruction about implicit bias with training in specific strategies (Forscher et al. 2016, Divine et al. 2012).

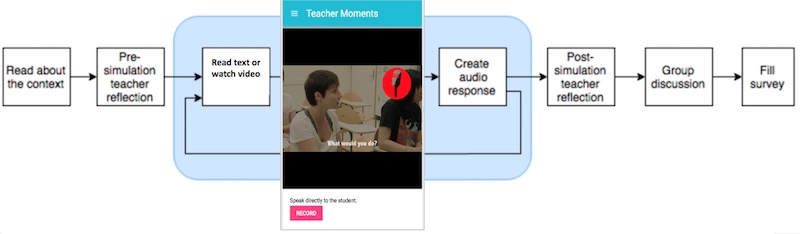

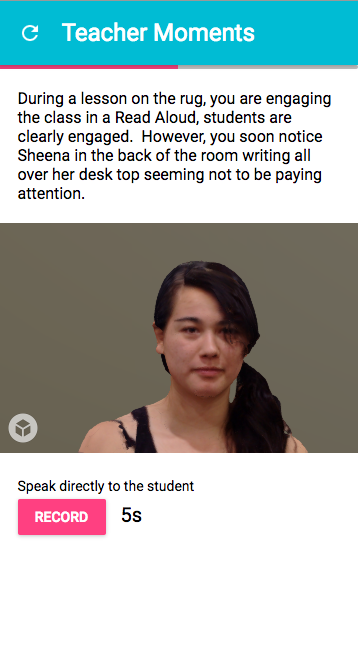

Within the MIT Teaching Systems Lab, our work is focused on creating practice spaces for teachers, and we’re working specifically on creating interactive case studies for teaching situations that might reveal implicit bias and provide opportunities for teacher to rehearse strategies for reducing bias.

These are situated within courses in teacher preparation programs, or professional development experiences:

Try out interactive case studies

What are some specific strategies teachers can practice?

- Check out the Critical Practices for Anti-bias Education and Anti-bias Framework for professional development lessons, materials and webinars from the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Teaching Tolerance project

- How do I know if my biases affect my teaching? from the National Association for Multicultural Education

- Unconscious Bias: When good intentions aren’t enough (Fiarman 2016)

- Student Engagement Strategies Guide

- Apps for Social Justice: Motivating Computer Science Learning with Design and Real-World Problem Solving

- Closing the Racial Discipline Gap in Classrooms by Changing Teacher Practice (Gregory et al. 2016)

- Complex instruction focuses on and social status issues in collaborative group work

In Computer science

- Tips for Reducing Bias from csteachingtips

- Practice with problem statements about women and technology from the National Center for Women in Information Technology (NCWIT)

- EngageCSEdu has excellent Engagement Practices and Instructional Materials

- Pair programming improves student retention, confidence, and program quality (McDowell et al. 2006)

- Two middle school students describe pair programming

How can we help students improve?

Cooperative learning has been the most extensively studied prejudice reduction techniques in the field, particularly variants on the Jigsaw technique (Aronson et al. 1978). This approach involves shifting “from a competitive atmosphere to a more cooperative one” by restructuring the classroom into diverse small groups. It was initially developed to improve classrooms that were being desegrated.

Several meta-analyses have been conducted on cooperative learning, and have consistently shown that they impact positive peer relationships and helpfulness (Johnson & Johnson 1989, Roseth et al. 2008, as cited in Paluck and Green 2009)

The Southern Poverty Law Center’s Teaching Tolerance program provides several classroom resources for student experiences, organized by grade level and subject.

What else can we do?

A lot! While we’re focused on improving equity in K12 STEM teaching, and helping teachers prepare and practice to create more equitable classroom communities, many other people are working on other aspects of these problems.

There’s lots of work to build the capacity of teacher preparation programs in teaching computer science and embedding computational thinking:

- Certificate in Computer Science Education from St. Scholastica

- WeTeach_CS from UT Austin’s Center for STEM Education

- Foundations of Computer Science for Teachers online course

- Alliance for California Computing Education for Students and Schools

And many efforts to increase access for students:

And researchers are working to investigate how teachers can best promote access and equity:

- Jason Okonofua, UC Berkeley

- Justin Reich, MIT

- Sepehr Vakil, UT Austin

- Rochelle Gutierrez, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign

Where can I learn more?

- Racial Disproportionality in School Discipline: Implicit Bias is Heavily Implicated (Rudd 2014)

- Diversity Gaps in Computer Science: Exploring the Underrepresentation of Girls, Blacks and Hispanics (Google, 2016)

- Black Girls Matter: Pushed out, Overpoliced and Underprotected (Crenshaw 2014)

- Women and science careers: leaky pipeline or gender filter? (Blickenstaff 2006)

- Google’s Computer Science Education Research

- https://code.org/diversity

- State of the Science: Implicit Bias Review 2015 (Staats)

- Unconscious Bias at work (Google)